Another faculty job market anecdote

Intro

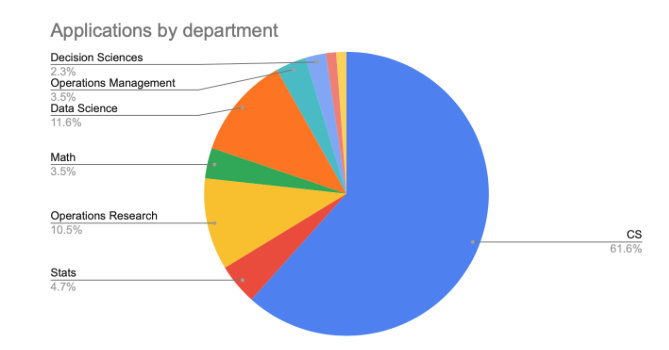

I went on the 2023-24 academic job market, mostly in Computer Science, but also applied to some positions in Operations Research, Data Science, Math, and Statistics. I learned a lot along the way, and am stoked to be coming out of the job market with my current position. I’m writing this to share some of my experience, but as with all advice, what worked well for me might not work well for you. If I say something that doesn’t feel right to you, feel free to ignore it. I applied primarily to faculty positions and went on the job market in the second year of my postdoc, so if you are navigating both markets simultaneously, things might be different. (Kate Donahue is writing a summary of her experience after going on both markets if that’s your plan; rumor is she’s willing to share if you ask nicely.) Warning: Survivorship bias. I got a job that I’m stoked about!

Everyone has different life factors affecting their decision (do you want to be in a big city; close to family; will your university support Visa applications?). In my situation, I had been dating my partner for a little under a year when the job market started, and her job prospects are best in Boston and the bay area. With my family being in Boston, I had a strong preference to stay in the area, but applied broadly since my relationship was relatively young. The preference to stay in the area led me to apply to some positions that I wouldn’t have applied for if they were in other locations (more on this later).

Evan Peck has a great blog post discussing the academic job market for liberal arts colleges, and in it, he describes the rich spectrum (notably not a dichotomy) of the expectations on research vs teaching. I view myself as sitting on the research-learning middle of that spectrum: I wanted to be at a university that would support my research agenda, but didn’t place such high emphasis on research output that I felt pressured to publish work that doesn’t feel complete or fully understood. My goals are to do good science, and for me, that is a slow process. I’ve tried rushing projects before and it’s marked some of the lower points in my research career.

Other references that I looked to during the job market (and will often defer to here):

- Kira Goldner

- Nikhil Garg – more OR oriented

- Elissa Redmiles and Nicolas Papernot

- Shomir Wilson

- CS grad job and interview guide – slightly more liberal arts focused, but contrasts the markets well!

- Liz Bondi-Kelly

If you have other aspects of the market that you want me to write more about, I’m happy to go into more detail. Just let me know what I should add!

Life outside of the job market

One of the things I am happiest that I did was tried to maintain a semblance of normalcy in my life outside of the job market. In the lull between October and December, I ran my first 50 mile race, which had been a goal of mine for a while. Training for such a big event required enough dedication that I at least couldn’t let work take over my weekends, and usually had me outside and running for ~an hour a day during the week. This is not to say that everyone needs to take up distance running, but having a commitment outside of work that I was held accountable for really helped me take my mind off of job applications.

Choosing a market (or two)

My work straddles Algorithmic Economics (aka EconCS) and Machine Learning Theory, which gave me some flexibility on how I could present my research ideas when talking to a future colleague. However, looking at my CV without talking to me, I look much more like a CS candidate: I had one major journal publication, and most of my other publications are at conferences like NeurIPS, ICML, and COLT. I also decided to primarily focus on the US market, since most of my roots are here.

I decided to apply to both OR and CS programs (plus a small handful of others), but had much more success with CS programs and virtually none with OR. I think this is in part because of how my CV reads. But in reality, when I really think about the questions that get me excited, these are more CS questions than OR questions, and this probably reflected in my materials implicitly.

Market timelines

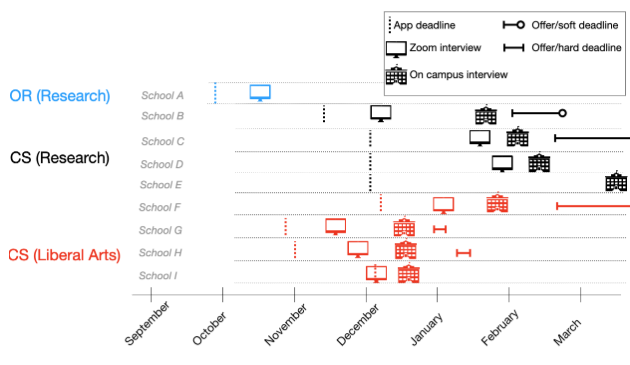

One thing to note is that different job markets have different timelines, and can make the job market play out like a real life prophet inequality. I interacted with 3 markets on slightly different timelines: the CS research market, the CS liberal arts market, and the OR market. I would recommend keeping this in mind: if you’re not excited about a liberal arts job, I would recommend not applying to the liberal arts positions even if the cost of application feels so small. When I say excited, I mean your utility should be above the optimal stopping threshold

CS Research: Applications were generally due in early December, and if I heard back from a program, it was most often in January or February, but had some Zoom interviews in the fall.

CS Liberal Arts: Applications are often due in October, with Zoom interviews starting as early as November and on campus interviews in December. I had two liberal arts offers, the latter of which exploded in mid-January, so I had to make that decision before I had even done any on-campus interviews.

OR: Some programs had INFORMS deadlines in October but “official” deadlines in December. From my understanding, you should hit the INFORMS deadline. Again, I wasn’t very successful in this market, so the rest of my discussion will probably not go into detail here.

Making friends!

The job market is not a zero-sum game. It can feel that way especially if you have any constraints at all, or impostor syndrome that leaves you afraid of not having any offers. I was very fortunate to have friends who shared job postings with me, did materials exchanges, and just generally commiserated. While many of us sat in the broad area of EconCS, it was comforting to realize that we all filled different niches and appealed to different markets. For example, some of these friends were much more successful on the OR market than I, but I was (sometimes) attractive to schools looking for ML theory candidates.

One of my deductions from the job market is that smaller departments often have to be more careful about diversifying their faculty expertise, but many large departments are indifferent. However, this isn’t always true: for example, while Francisco and I are both in the EC and EAAMO communities, we’re both going to be joining BC in the upcoming year, and it was so exciting and encouraging to realize we both had offers at the same time.

Other members of my job market network and information sharing included Kate Donahue, Bailey Flanigan, Naveena Karusala, Francisco Marmolejo Cossio, Lily Xu, and tangentially Jess Sorrell, who is a queen of job market crowdsourcing. I had met all of them through conferences or locally before starting the job market, but that’s not a requirement for job market friends. It was also really helpful to have friends and mentors who had recently gone through the market, but were on the other side. (I know this paragraph is just one big love letter to a solid chunk of my support system.)

Choosing letter writers

For academic jobs, letter writers are often (from my understanding) a large part of the application dossier. The main advice I have here is to ask your letter writers early! I asked my letter writers in early August, and I think that timing was a bit rushed for OR positions. For CS, this generally seemed to give enough time, but even earlier couldn’t hurt.

For my letter writers, I used this anonymized doc with my letter writers to keep track of which schools they still needed to upload letters for. I tried to send “ping” reminders a week before deadlines came up, but this turned into a semi-frequent digest of updates. With that said, it was a semi-team effort to keep this doc updated at times, and some application portals are better than others at letting you know the status of your rec letters.

Application materials

I’m really bad at working under pressure, so I planned to start my application materials early and iterate often. I started outlining and working on my materials on Friday afternoons (my least productive research time) over the summer before I went on the market. This left me with a preliminary version by September, and buckled down more seriously to focus on my statements (~10 hours) in the first half of September. At that point, I reached out to some of my mentors and friends for feedback. They gave lots of helpful comments and small iterations on my materials kept happening incrementally throughout the rest of my applications, but I was somewhat close to a steady state by mid September. This was nice because I was able to share a rough version of my materials with my letter writers so they understood how I was thinking about my work and presenting myself.

Here are examples of my statements and application materials: research statement, teaching statement. Please feel free to email me for a copy of my diversity and inclusion philosophy or cover letter. I feel weird about sharing these publicly.

Application breakdown

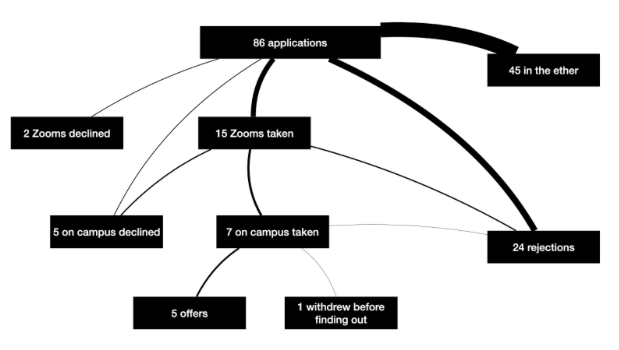

At the end of the day, I applied to 86 jobs, 84 of which were faculty positions and 2 postdocs. The large majority of these were in CS departments, but this was trailed by Data Science and OR. Of the 86 positions I applied to, 10 were more teaching-oriented positions, and the other 76 were more research oriented (from my understanding of the positions). In my opinion, 86 positions was way too many for me. Do what feels right for you, but I think 30-60 is much more reasonable if you’re really dedicated to academia.

Zoom interviews

Zoom interview season is where the job market started to take over my work days. In all, I took 15 Zoom interviews: 6 were at teaching schools (which took place between early November and early January), and the other 9 at research schools took place between early December and mid January. One school did invite me straight to an on-campus interview in mid March, but I had already accepted my position at that point. Most of the interviews had 3-5 faculty members present, who introduced themselves and asked a variety of questions, which I will dive into later.

Most interviews were scheduled for 20-30 minutes, though one was scheduled for an hour. Some ran over on time, and I felt too awkward to excuse myself, but I intentionally scheduled 20 minutes before the interview to review notes and calm down, and 30 minutes after as buffer time and “unwinding” time when I could.

A things I did that I felt helped me (though I definitely had some interviews where I didn’t put my best foot forward):

- Make sure you have a quiet space with reliable internet.

- I took one interview from my apartment and my Wifi cut out more than it ever had on a Zoom call, and I was incredibly flustered. After that, I took almost all of the rest of my interviews from my office. I’m fortunate that my (shared) office has a conference room that my labmates yielded for interviews. If your university has a room reservation system, take full advantage!

- Depending on which schools you apply to, you might have a school try to schedule an interview while you’re traveling. Personally, I would try to avoid this as much as possible. Interviewers know you’re busy and interviewing at other schools, so if you mention that and share that you want to be fully present and engaged in meeting them, folks tended to appreciate that.

- Schedule to your strengths (as much as you can).

- I know I work best in the mornings, so I tried to schedule my interviews for early- to mid- morning subject to time zone changes. Of course, it’s hard to wrangle 3-5 faculty together, so this isn’t always possible.

- I ended up rearranging travel plans after the holidays, but was too afraid to ask to reschedule my interview, so I had to take one Zoom interview from my parents’ bathroom to make sure no young children barged in. If it really comes down to that, I would highly recommend blurring your background if possible and making sure nothing in your background gives away the less-than-ideal circumstance you find yourself in.

- Do your research

- “Why did you apply for a position at X university?” This was probably asked in every interview. Have an answer ready.

- Department cultures are very different, and a lot of that can be deduced from some sleuthing online. I emphasized searches on ML, theory, or algorithms. If the listing has a specific focus, there’s surely some reason. If a school wanted someone for algorithms, try to see if you can find who taught algorithms 3 years ago– is this person in industry now? Teaching other classes? Has the person teaching this class rotated every semester? If so, this might be a good case for you to establish yourself as “the” algorithms professor… if you want to be.

- Sometimes, the entire search committee would be cc’ed on my Zoom interview invitation. Take the time to look at their websites, and get an understanding of who will be interviewing you. For schools I was really excited about, this ended up being about a 2-3 hour time investment. As I got overwhelmed by the process, this became about 1 hour of prep per interview.

- Have questions ready (that aren’t easily google-able) and show your genuine curiosity.

- Some standard things I usually wanted to know included the teaching load, where students are often heading after graduation (grad school vs industry), what are the opportunities for internal funding from the school? These can be deduced with research, but I think it is still good to confirm or see how often people take advantage of the offerings. You can ask something like “Poking around on the website, I noticed the X institute seems to sponsor interdisciplinary research at the University. Have any faculty taken advantage of this funding?”

- One example of a question I asked that signaled my interest at BC was that I knew they didn’t have a PhD program at the time, but we are in the process of establishing one. I asked where in the process they were with that, and what they would hope the program looks like in years 3-5, as well as at its steady state.

- Don’t be late!

- This goes without saying, but with tech issues and Zoom permissions… be ready 10 minutes early and sign on 5 minutes early. It runs the risk of small talk (which only happened once), but usually the committee will have you in a waiting room until they’re ready for you anyways. I had a technical issue where the email invited to the Zoom link was a different alias than the alias affiliated with my Zoom account. Thankfully, we were able to diagnose this in the minutes before the interview.

Some interviews were hosted by a panel of faculty in the same room, which was extra nerve-wracking for me as an interviewee, since I felt like I wasn’t privy to lots of non-verbal communication. In general, I felt most comfortable if there was some slight flexibility on “the script,” but some schools explicitly stated they wouldn’t ask follow ups in the name of equity, so everyone prompted the same questions.

Some questions I got included…

-

Why X university?

-

Your background is in CS? Why are you applying to DS/OR?

-

What “standard” class would you teach? Topics class to design?

-

Our university is in [great location]. Who would you collaborate with outside of university in [great location]?

-

What have I done to make my community more inclusive to historically marginalized folks?

-

What is the first grant I would apply for? What is the title of my NSF CAREER?

-

Who would I apply for funding from?

-

How would I structure my research group? What do I see as my steady state?

- This is, BTW, a great question for you to ask as well!

-

In one interview, I sent over a paper of mine in advance and we walked through the contributions and proof intuitions together

Job Talk

In general, Dan Larremore has a great reference on giving academic talks. I think most of the advice is generalizable to the job talk, despite his example of a 10 minute talk.

Most job talks (all of mine) are scheduled in a 1 hour slot, and most faculty will try to attend most of them, which, in my interpretation, meant I had the half-attention of a lot of people (as opposed to the full attention of a few people). I tried to structure my job talk so folks could re-engage easily enough if they dropped off, and I aimed for the talk to be 45-50 minutes long. I was given the advice to generally keep things as simple as possible, but to do one deep dive “behind the curtain” so folks who were interested could get the flavor of how I approach my research from a more technical perspective.

Three schools had me give my job talk early in the day, before any one-on-one meetings, and three had me give it mid-interview. (One school had me give a teaching talk instead.) Giving the job talk early was great for one-on-one meetings, since discussions could usually skip over the “what’s your research” elevator pitch. However, one job talk that was at 9am was filled with an audience that was visually not awake yet and/or on their laptops before the talk even started, and I didn’t reap that benefit of the early talk.

Some examples of job talks include: Kira’s, Elissa’s, and my slides.

On-campus interviews

On-campus interviews are very helpful to help you figure out if you’ll be happy in a department or university. However, it comes at the cost of lots of travel. I did 3 on-campus interviews in one week (two were local), and learned my lesson the hard way. After that, I pushed to not have more than one on-campus interview per week. This actually helped when I was trying to add in some Zoom interviews later on in my process, but if needed, I think two is possible (depending on if they are one or two day interviews).

Some schools booked accommodations for me, and some reimbursed me for booking my own flights. One upshot of the latter is the flexibility to pick your own flights and times that work for you, but convenient flights are more expensive. Overall, I spent about ~1200 out of pocket that I was later reimbursed for, but the administrators I worked with on these reimbursements were so helpful and speedy in processing everything. (Make sure to thank them a little extra!)

I’ll defer questions to ask and things to expect to Kira’s and Liz’s blog posts, since they did a wonderful and comprehensive job describing the process.

Tech issues encountered

Different schools might have different preferences for how you present. Two schools had me join the Zoom for the hybrid part of the seminar from the in-room desktop, and the rest had me present off my laptop. In one talk, my laptop froze twice when I put Keynote into full screen while displaying on the monitor, and we had to adapt. Also, not fully a tech issue, but if you have a teaching talk, it’s worth checking in advance if there is a whiteboard/markers available if you want to use one.

Packing list

I made some stops at stores while on the interview, but any extra stop on the road is just a little more exhausting.

-

Adapters

-

Laptop

-

Flash drive (with copy of slides on it! Also have a copy of slides on your Dropbox/iCloud/Google Drive)

-

Pencil/notebook for notes

-

Chapstick

-

Tide pen

-

Throat coat tea (I didn’t get sick, but my throat got sore from talking so much)

-

Interview clothes (plus extra top if room) and shoes

-

ID/wallet

-

Water bottle, electrolytes

-

Clif bar/snack

-

Ibuprofen/Tylenol

Things I didn’t pack but wouldn’t be bad to bring:

-

Blister pads

-

Anything you need to sleep well

Offers and Negotiating

At this point in the process, I was so thankful to just have job offers that I was really excited about, I felt really awkward negotiating for anything. The PhD was my first job (with standardized pay), and I had an institutional postdoc that I couldn’t negotiate salary. In hindsight, I think there was still space to negotiate on those in the past, but I didn’t, so faculty offers were the first time I had ever negotiated.

The first thing that surprised me was that while your offer usually gets communicated to you through either the department chair or search committee, any negotiating I did often went through the dean. Some places reached out to ask what I wanted in an offer and put negotiation on the table before I had the official offer, while others didn’t explicitly put negotiation on the table in the offer. Even those that didn’t were still open to negotiating though. My main advice here is to be kind, but advocate for yourself. If you are requesting something, I felt much better asking if I was able to articulate why I needed it.

Ultimately, I asked for 3 things when negotiating my offer, and was only granted one of the three. For the two things I wasn’t granted, I was given (very reasonable) reasons why things couldn’t happen.

For additional references, see Elissa and Nicolas’s blog post. I also used the H1B database at some universities to understand recent salaries that had been accepted at some universities.

What to negotiate for

While salary is maybe the most obvious thing to negotiate for, there are other things that will make your life better:

- Salary

-

This one is most obvious, but I will make the point that most raises are percentage based, so the higher your salary starts, the more your raises increase as well. Most salaries are offered as 9 month salaries (though some schools I interviewed with had 10 month contracts). Make sure you understand how many summer months are permitted. This isn’t usually negotiable from my understanding, but worth knowing.

-

My initial offers ranged from 85k (10 month) to 136k (9 month), with research universities being higher than teaching-oriented positions.

-

- Startup (and bucket/timeline flexibility)

-

Some offers will have expiration dates on startup, while others don’t. This timeline might be a bit harder to negotiate for if it is a university policy, but it doesn’t hurt to ask for more time. The goal of your startup is to help you get your group started, so it makes sense that it often expires. But if it doesn’t, then your startup might be more of a nest egg in case there’s a phase where grant funding doesn’t come through.

-

Some universities will also have buckets for the budget breakdown, while others give you a lump sum for startup.

-

Bucketed startup points

-

Summer salary / student hours

-

Sometimes this is included in the startup package, but sometimes its separate. One thing to distinguish is whether student hours are in the form of RA or TA slots. Some universities have (# PhD students) » (# TA slots), so making sure your students are guaranteed some of these precious TA slots can be helpful, but comes with more external expectations of your students than an RA.

-

Many universities have limits on the number of summer months you can take, but if you are given summer salary, it might be for a fixed number of months.

-

- Equipment

- As a theorist, I don’t have many equipment needs. Many contracts will have an explicit technology policy (e.g., new laptop every 3 or 4 years), which was most of what I needed. If you are in other research areas, this might be negotiated explicitly, or negotiated into your startup. I’m not very helpful here.

- Conference travel / publication fees / professional memberships:

- If you publish in journals that have publication fees, this can be negotiated for.

- You might negotiate travel for (for example) X international conferences and Y domestic conferences, either for you or your students.

- IEEE, ACM, INFORMS, etc. memberships are expensive. Negotiate for you (and maybe your students as well as they sign up for conferences?)

- Teaching load and teaching release:

- Some universities will let you “buy out” of courses, while others prefer you don’t. It’s all discussion worth having (either in negotiating or with current faculty). Most offers I’ve seen offered one semester of teaching release in the 3rd or 4th year after a mid-tenure review, so it’s not unreasonable to ask if one is possible.

-

-

Navigating multiple offers

Yay! Not only have you gotten an offer, but you’ve gotten multiple! And now you have to choose between many great places! Most universities are on slightly different timelines, and coordinating with all of them might require some frank and honest communication. In general, folks tend to be very understanding that you need to do what’s best for you in the search process, and they want to hire people who want to be there. As a few department chairs reminded me, “if we pressure you into accepting our offer but you’re not happy and leave after a year, that’s a lose-lose because we have to fill your spot again.”

Smaller departments tend to have less budget flexibility in the number of faculty they hire. If a department has 10 lines open, and they accidentally hire 11, this is not as bad as a department that has one line open having two faculty accept offers. My best guess is that, for this reason, smaller departments tend to give exploding offers more than larger departments. I had two exploding offers (10 days and 3→5 days), and three offers that asked me to let them know what I’m thinking within two weeks. The exploding offers came before any of the on-campus interviews from my other offers, so I had to make the (very difficult) decision to let both of them explode before I had any other offers in hand. This is the main reason I would advise against going on both the liberal arts and research markets: the timing really doesn’t line up that well.

In these cases, I kind of feel bad that I had applied to these positions in hindsight, but my decision to let the offers explode was influenced by some positive signals I had gotten from other on-campus interviews lining up.

As per usual, Kira has great examples of emails that she wrote when she was on the market and navigating this space.

I’m including a noisy example of my job search timeline below. More interview offers came in later in this cycle, but I didn’t go fully through the interview process to have full timelines.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: